Sutro Tower

Is There Such a Thing as a Favorite Antenna?

By Judah Mirvish

Introduction

San Francisco’s modern history began inland of the city’s current northeastern corner. The Portola expedition up the Californian coast marked the first overland visit to the Bay Area by Europeans. It led to the establishment of a settlement, then named Yerba Buena, between the sites of Mission Dolores and a Spanish garrison in the Presidio. The outpost, along with the remainder of Alta California, was claimed by the United States in 1846 in the course of the Mexican-American War, and renamed San Francisco in 1847. Development of the city began in earnest with the outbreak of the Gold Rush in 1849. A 25-fold increase in population led to the infilling of Yerba Buena Cove to accommodate new arrivals, in some cases, housing homes or businesses in or on top of the very ships that brought those people in. From early on, Market Street served as a central spoke for the city, beginning as a wharf in the Bay and running diagonally inwards towards the center of the peninsula, with streets arrayed in a grid with a north-northwesterly orientation above it and a northeasterly orientation below. Over more than a century, the city expanded west and south from its original city limits of 20th Street and Divisadero/Castro, gradually building out to its modern boundaries near Lake Merced.

The western half of the modern-day city was developed from sandy, inhospitable terrain, and would only fully reach a more-or-less complete version of its modern map in the 1970s. Despite the installation of large-scale infrastructure to allow transportation of citizenry back and forth from the city’s periphery (streetcars beginning in the aughts and the Central Freeway in the 1950s, among others), San Francisco would retain a populous urban core in its northeast quadrant, giving way to increasingly small and suburban developments the further you went in either opposing direction. These trends shaped the skyline, with none of the city’s 60 tallest buildings laying past Market and Van Ness. Particularly given the hills, many areas in the western half of San Francisco lack any visual evidence of a nearby skyline, downtown, or even a major urban center. This was even more true than today in 1971, when after more than a decade of planning, construction began on Sutro Tower. By the time of its first broadcasts in 1973, the steel behemoth would stand nearly 1000 feet tall, not even accounting for its hilltop location – itself more than 800 feet above sea level.

The opposition that shaped the complex development of Sutro Tower would also color its initial public reception. Angular and utilitarian, Sutro Tower was opposed by neighborhood advocates, environmental watchdogs, and Victorian traditionalists alike. The city’s most famous journalist, the Chronicle’s Herb Caen, wrote of expecting it to “stalk down the hill to mate with the Central Freeway.” Neighborhood relations did settle down from an initial (relative) frenzy, as the media conglomerate who owned and operated the structure worked on ironing out points of contention such as nighttime lighting, whistling anchor wires, and paint spatter across the homes of the greater Twin Peaks. It has nonetheless been an unexpected journey that has transformed the tower from the “Iron Monster of Mt. Sutro” – an “eyesore” tolerated for its irreplaceable contributions to modern city living – into a San Francisco icon, not only for the low-lying western districts over which it singularly soars, but of the landmark city at large.

San Francisco’s lone snowstorm, 2/5/1976

The Name Behind the Tower

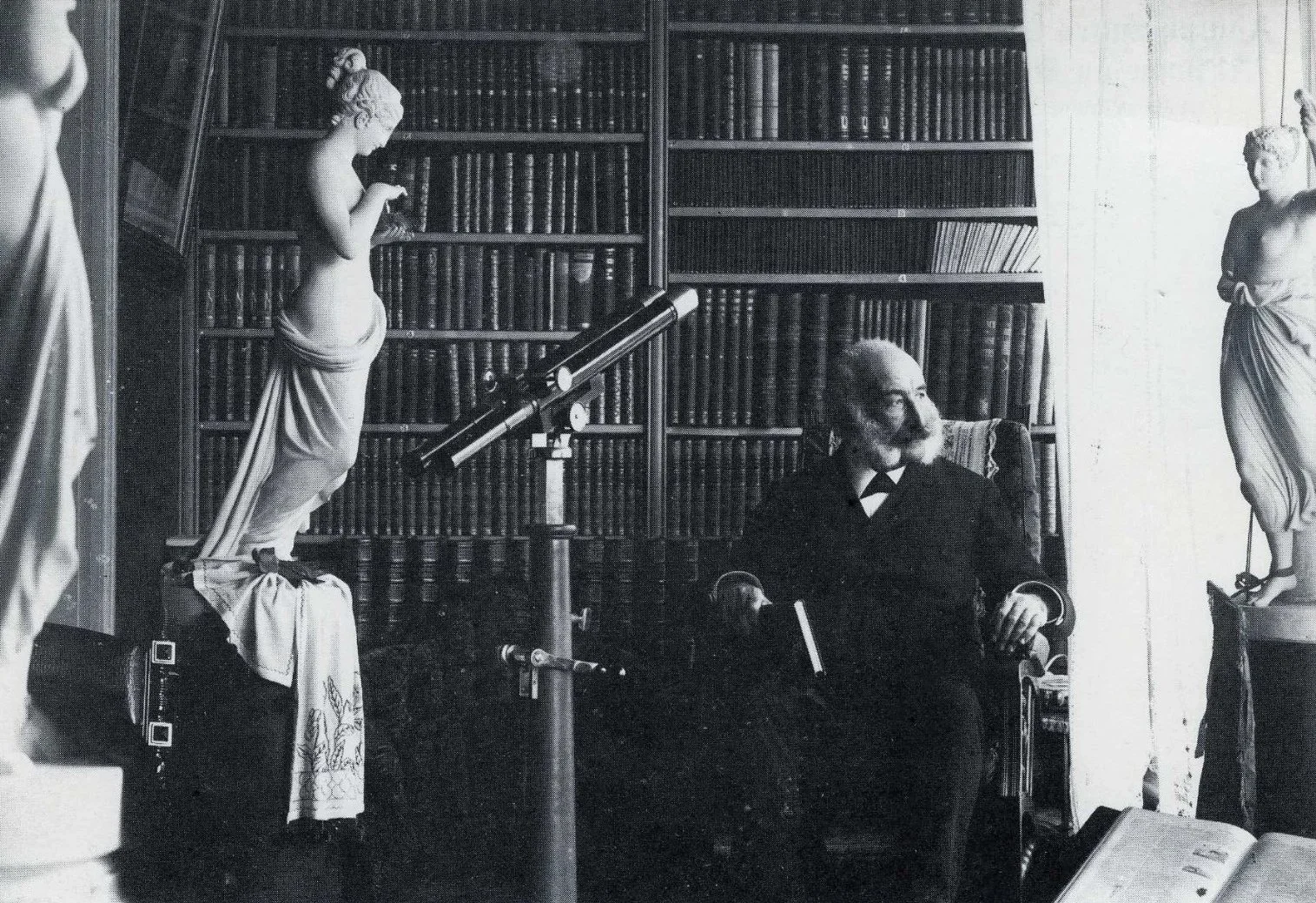

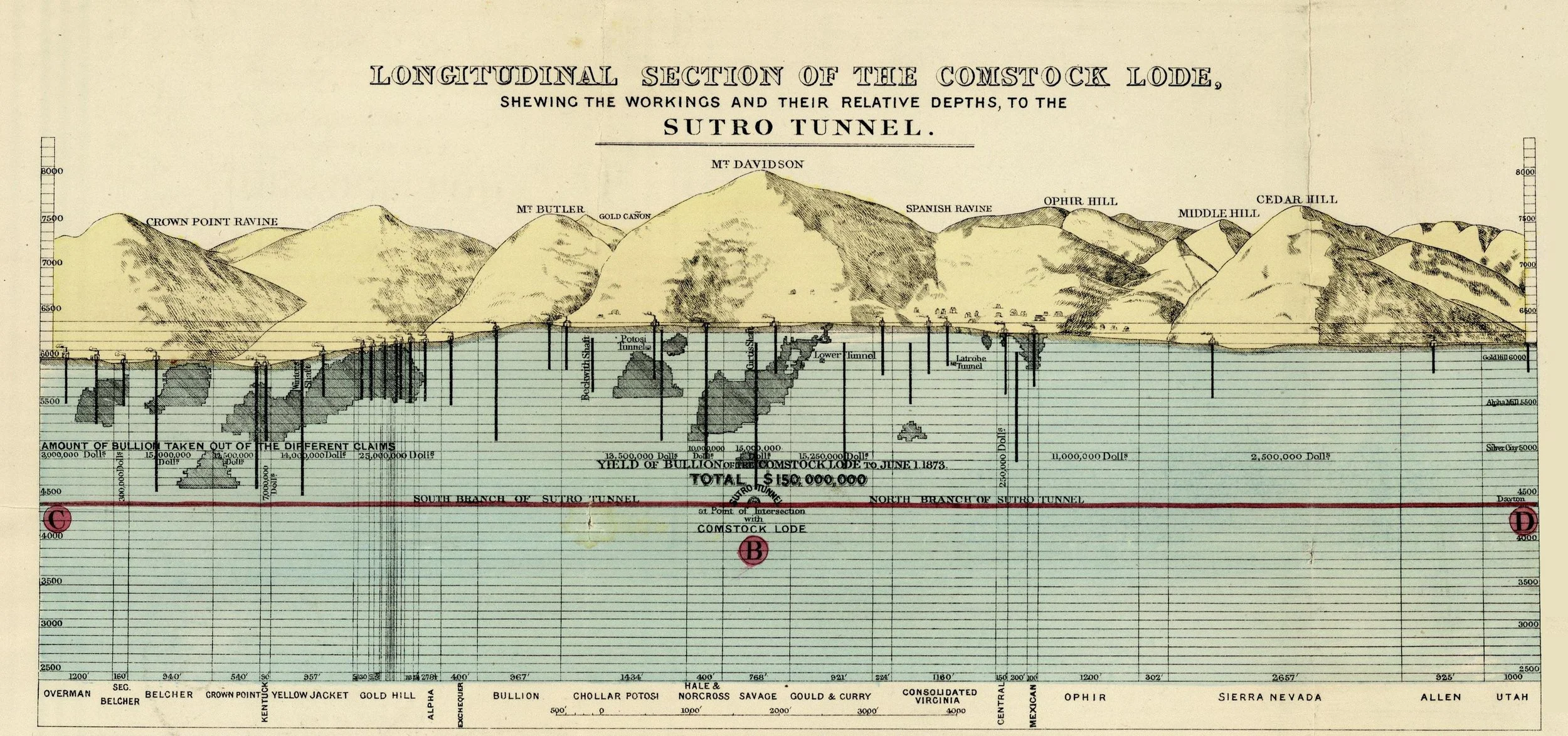

Adolph Sutro (1830-1898) moved to the United States with the rest of his Prussian Jewish family in 1850, 3 years after the death of his father, a clothing manufacturer. While the remainder of his family settled in Baltimore, Adolph would travel to San Francisco in 1851 by way of Panama, hoping to sell European luxury goods to an anticipated community of nouveau-riche gold miners. While these plans failed to fully materialize, Sutro made enough money to establish himself as a tobacconist and begin building a fortune of his own. Following a failed attempt to cash in on a second gold rush in British Columbia, Sutro pivoted precious metals to silver and moved to Virginia City, NV following the discovery of the Comstock Lode. After again laying down roots by selling tobacco, Sutro would ultimately spend 19 years in Nevada devising and seeing through to completion the Sutro Tunnel: a 4-mile-long tunnel built between 1869 and 1878. The $6.5 million undertaking required Sutro to curry favor with Nevada legislature and fight pushback from the Bank of California, but eventually secured Sutro his fortune, earning him $10,000 a day in rent from the mine owners who relied on the ventilation and drainage the tunnel afforded to keep their business viable. Sutro returned to his family in San Francisco in 1879, and spent the remainder of his life investing his fortune into San Franciscan land – owning, at his peak, almost a tenth of the territory in the city – and infrastructure.

Much of his holdings were located in the city’s barren western reaches. In the latter stages of his life, this came to include most of his great public projects, including the Cliff House, Sutro Baths, and Sutro Heights Park. These activities would certainly benefit Sutro, materially and financially. His latter years, for instance, were spent living in an opulent mansion in a 22 acre plot overlooking the Pacific Ocean. However, he was also openly committed to benefitting his fellow San Franciscans. He opened the grounds of his estate to the public and maintained low admission prices to Sutro Baths, and while he profited off of the railways he built to transport San Franciscans out from downtown to the ocean, these actions were also pivotal steps in the eventual settlement of the Richmond and Sunset districts. In a similar vein, Sutro was an early conservationist, campaigned for nature preserves, and reportedly had 40,000 trees planted, including a eucalyptus grove on Mount Sutro that survives to this day – though he was also noted to receive tax exemptions on any land he owned that could be designated “forested.” All told, Sutro was held in high esteem by fellow San Franciscans. Representing the Populist Party, Sutro was elected handily in 1894 as “the first Jewish mayor of a large American city,” and served in office for 2 years prior to his death in 1898. Following his death, Sutro’s complex estate was contested between, among others, Sutro’s ex-wife (who had divorced him in 1880), their 7 children, Clara Louisa Kluge (who claimed to be his common law wife), and her 2 children (whom she reported he had fathered). The family’s dwindling fortunes and bequests to the city, University of California, and others led to the gradual dismantling of the estate in the early portion of the 20th century.

Mount Sutro persists much as it was left by Sutro himself at the time of his death: covered in eucalyptus trees and owned by UCSF. Sutro Tower itself is situated not on Mount Sutro, but on an adjacent hill, sitting to the southwest in the direction of Twin Peaks and falling short in elevation by about 80 feet relative to sea level. Sutro Tower’s modern day access road, La Avanzada, derives its name from a mansion built there in the early 1930s by Adolph Sutro’s grandson, Adolph Gilbert Sutro. Born to Edgar, the 6th of the 9 children believed to belong to Adolph the elder, the younger Adolph shared at least some of his namesake’s entrepreneurship and flair for the dramatic, serving as a mechanic for the Wright Brothers, receiving “License No. 1” as the first authorized pilot of a “hydro-aero plane” in the United States, and managing Sutro Baths before retiring to a fairly secretive life of luxury. He lived as a “bachelor scion” in La Avanzada with his mother until they sold the home in 1948 to move to Southern California.

The home was purchased by ABC affiliate KGO-TV as a base of operations, and after winning approval to convert the property’s zoning from residential to commercial, used it to house both studios and broadcasting equipment. Taking advantage of one of the highest elevations in the city, KGO built a 580-foot-tall broadcasting tower on La Avanzada’s grounds. They would sent out their first broadcast in 1949. KGO was joined by San Francisco’s only older television station, CBS affiliate KPIX, in broadcasting from La Avanzada in 1951. Two years later, KGO moved its production headquarters to the Tenderloin, leaving La Avanzada as a minimally staffed, largely automated broadcasting hub. By the time Sutro Tower had at last approached the start of construction in 1969, the remnants of La Avanzada were deemed “a fire trap and a mecca for vandals,” its grand front windows having been smashed by rocks and boarded up. A select few of the architectural details, such as a spider-themed stained glass window, were salvaged from the site, but the remainder was torn down as “part of the agreement with the city” prior to erecting the tower.

Waves and Hills

Radio broadcasting began in the United States in earnest in the early 1920s. The Bay Area was an early hub of radio activity, with San Jose-based transmissions by pioneering broadcaster Doc Herrold dating back as far as 1912. Starting in April 1920, Lee DeForest installed a 1000 watt transmitter on the roof of the California Theater at 4th and Market, and broadcasts from the downtown-based station would continue for a year and a half before DeForest relocated operations to Rockridge, Oakland. The station would develop a “large and loyal following in the Bay Area, and could be received clearly at night across all of the Western states.” Over the coming decades, radio broadcasting evolved from an experimental, individual-driven enterprise into a more strictly-regulated affair operated by larger media consortiums. These changes heralded a shift from localized, small-scale programming towards regional, and eventually national, broadcasts of shared material to progressively larger and broader audiences. By the late 1920s, major corporations like NBC and CBS were using phone line technologies to transmit national programs to local radio affiliates, who would in turn broadcast the shows to local listeners.

Early forays by radio companies into television broadcasting were defined by the limitations of the more technically demanding medium. The need to concurrently transmit signals of both audio and visual information multiplied the demands placed on equipment. The technical foundations for television broadcasting were laid in the late 1920s, with breakthroughs such as the development of coaxial cables by Bell Laboratories. More than a decade later, in 1940, milestones in early TV included an intercity NBC broadcast from New York City to Schenectady, and transmission of the Republican National Convention from Philadelphia to New York. Development of broadcasting technology and a national network of program producers and subsidiaries would take off following the end of World War II.

Eventually, direct-to-home broadcasting technologies such as cable and satellite television would emerge as competitors to over-the-air television. However, these sea changes remained decades away as television came slowly to accompany, and eventually supplant, the radio systems that had spawned it. Major networks invested their resources into the then-nascent technology, having their affiliates stake claims to a local television frequency. These choices, made in the earliest days of TV broadcasting, would prove significant. Over-the-air television was restricted in its infancy to the very high frequency (VHF) range of 30-300 megahertz, in which the limitations of tuning equipment sensitivity dictated a functional maximum of seven TV channels that could coexist in any given locality: channels 2, 4, 5/6, 7, 9, 11 and 13. The first networks to arrive would retain a permanent leg up on stragglers. Beyond simply lacking longevity and name value, the competition would have to broadcast in the later-introduced ultra high frequency (UHF) range of 300-3000mHz, reception of which was not even mandated in television sets until 1964. In San Francisco, then, as in other cities, early competition in television included a small number of stakeholders with limited room for outsiders to find their way in.

San Francisco’s pioneering broadcasters would be forced to grapple with one technical problem surpassing that in almost any comparably burgeoning American media market: interference. Electromagnetic waves are defined by their frequency, and vary from one another in the degree to which they can be obstructed by physical barriers. Lower frequency waves, such as AM radio waves, can travel along the ground or be bounced downwards by the atmosphere, allowing them to travel long distances and largely evade obstruction. Higher frequencies, meanwhile, are subject to effects such as terrain shielding, in which dense objects like rock sitting between the source and receiver of a wave prevent it from passing through. As with light waves in the visible spectrum, the key to successful transmission of TV waves is a “line of sight,” or an angle providing unobstructed passage of the waves from their source to any device hoping to receive it. In general, the answer to interference is transmission from an altitude overlooking anything that might block a wave from reaching its destination. From the earliest days of radio, as antenna towers propagating across the world became road markers of modernization, it was understood that the more barriers an area included, the higher the source would need to be. Nearly every other proposed detail of Sutro Tower would eventually be changed, but from the very start, broadcasters in America’s (perhaps) 10th hilliest city understood that the solution to their problem would need to be very, very tall.

Turf War

By the mid-1950s, America’s still-expanding radio empire stood in proper competition with television, which had entered into its First Golden Age and begun to establish itself as the cultural staple it would remain ever after. It was understood within the industry that a taller tower than any existing in the Bay Area at that time was an inevitability. It was less certain where this would end up.

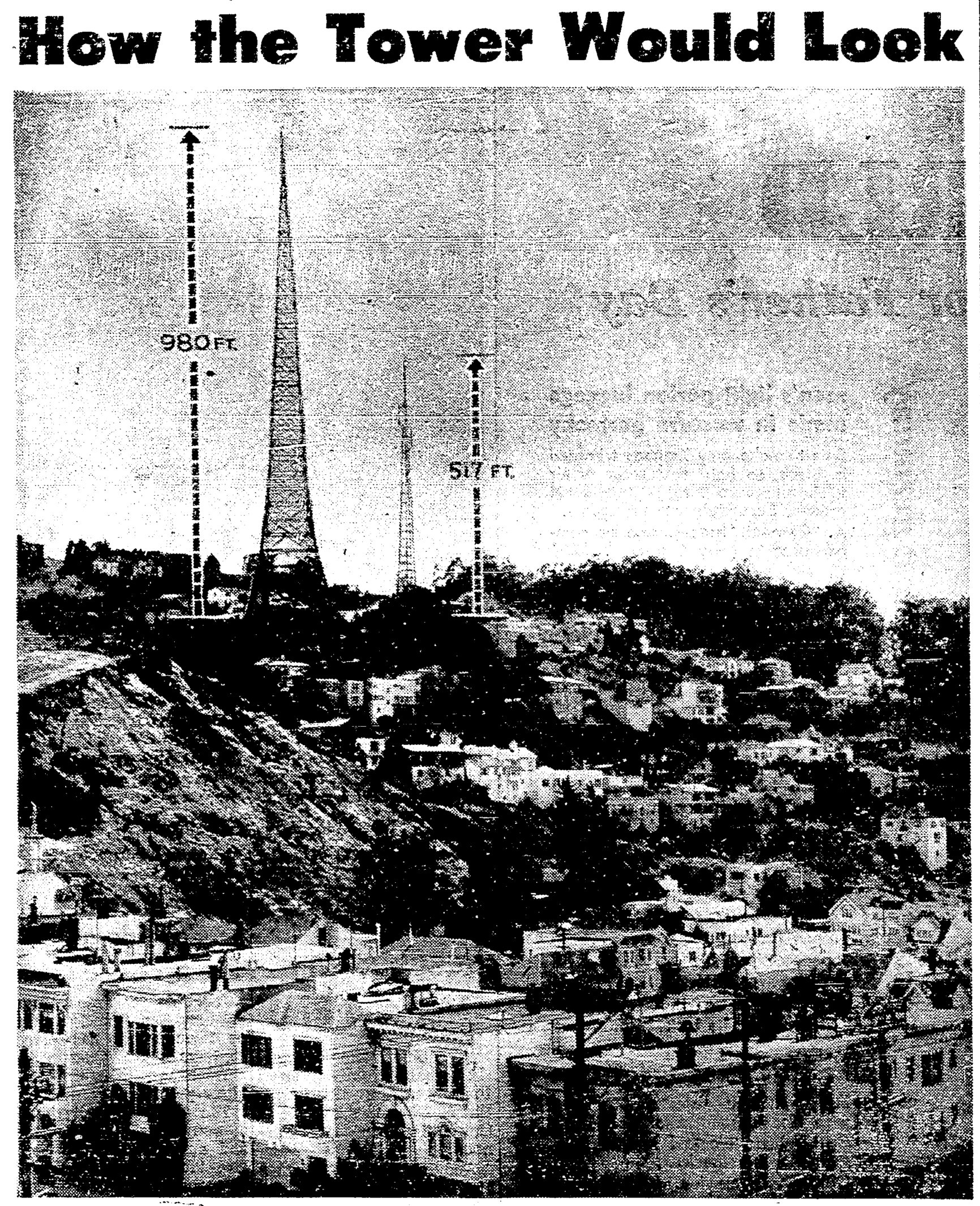

When ABC affiliate KGO had erected their 580-foot tower at La Avanzada in 1948, the structures of both broadcasting and postwar governmental bureaucracy were less complex than they would be less than a decade later. The altitude and central positioning of Clarendon Heights certainly made La Avanzada a strong candidate site if the existing tower were to be replaced, but the hilly Bay Area had no shortage of potential alternatives. San Bruno Mountain, south of the Cow Palace, would be the most prominent from the start. KGO first applied to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to upgrade its existing equipment at La Avanzada to a 980-foot tower in 1956. Meanwhile, NBC affiliate KRON applied for a tower location on San Bruno Mountain.

In 1957, the first series of what would ultimately prove to be more than 10 years’ worth of critical articles about the tower was published in the Chronicle. Writing under the byline “Opposition to KGO Eiffel Tower,” the paper reported on June 10 that “plans to pitch a steely structure atop Mt. Sutro the height and about the shape of the Eiffel Tower began kicking up a surge of opposition from residents in that area last week.” Cited opposing locals were not only named, but credentialed. Dr. Robert Lyon worried that the shadow of the behemoth would “decrease real estate values by $1000 a lot,” while engineer Byron Nishkian warned it would alter the “semirural atmosphere” treasured by those who had moved up the hill “because it is almost like country living.” The project was contrasted with KRON’s proposal, which was described as a “slender staff” to be erected in the “empty, uncluttered reaches” of San Mateo county, “instead of hoisting its metallic head above the quiet residences clustered by Mt. Sutro’s sides.” La Avanzada was pinpointed “in the heart of San Francisco,” while the San Bruno Mountain site was casually described as “south of the county line” – an unnamed other’s backyard, someone else’s eyesore. For emphasis, the “metallic snout” described on June 10 was depicted on June 11 in a half-page photograph, standing alongside its predecessor and dwarfing it in height and silhouette. This time, an attorney named S.M. Saroyan said, “The present towers stands out like a sore thumb – if they make it twice as high, it’s going to be terrible.” KGO was even accused of bureaucratic malfeasance, presenting arguments directly to regional planning subcommittees rather than following the submission protocol considered “usual in such cases,” as KRON has deigned to.

Following years of back-and-forth, a spate of Chronicle articles would appear again in 1962. In addition to the FCC, site planning had come by then to involve the then-Federal Aviation Agency (FAA), for whom the location of San Francisco International Airport – whose recently opened Central Passenger Terminal lay about 5 miles southeast – was of particular interest. That July, the FAA’s W. Thomas Deason presided over a hearing tackling the relative risks posed by each site with respect to “aviation hazards.” As the Chronicle noted, Deason “would not permit testimony of the effect the massive KGO tower would have on the neighborhood,” nor would he require KGO to respond to an inquiry over “what would happen should a Mount Sutro tower fall down” – despite, the article notes, there having been a “new grade school within a thousand feet of that tower.” Robert Hammett, an engineer called by KRON as a witness, was quoted suggesting that the San Bruno site would allow for a shorter tower nonetheless capable of greater broadcasting capacity due the absence of preexisting structures competing for space. He argued there would be no “compromises in performance” only if San Mateo won out; pointedly, this site was also described as the only solution allowing competing stations to coexist “on an equal footing.”

On July 12, 1962, suspiciously one-sided reporting at last gave way to an explicit endorsement. “The Chronicle Publishing Co. will never try to persuade city zoning officials to permit construction of a 980-foot television tower atop Mount Sutro. The Chronicle has deep roots in San Francisco, and this is a matter of the community’s esthetics.” They argued that the Avanzada proposal, described five years earlier as a “Sword of Damocles” local residents would be forced to live underneath, “does not belong in that area.” In December, The Chronicle reported that a restaurant could be build atop a tower project in San Bruno; where the Avanzada project had been compared to a space-intensive, rather Victorian Eiffel Tower, this prospective mountaintop viewing platform was compared to the slim, futuristic Space Needle, constructed that very year for Seattle’s World’s Fair.

Not every piece the paper ran depicted KRON in a positive light. Columnist Dwight Newton dedicated a November 1965 column to the infighting between KRON and KGO, blaming both for having “jockeyed for power as thousands of viewers suffered acute astigmatism of the sets for eight years.” A follow-up in February 1966 explicitly describes KGO as wanting to build on land owned by parent corporation ABC, and KRON wanting to build “on property owned by the Crocker Land Company.” The article credits ABC for foregoing cashing in on by-then significantly increased land value, instead not only agreeing to join a cooperative nonprofit with other TV stations to buy the land from ABC for its 1948 purchase price and manage the tower, but advocating for PBS affiliate KQED to be brought into the fold for free. Newton blames KRON for stopping construction through court action after everyone else was on board, and snarkily suggests that with flights from SFO rendering KRON’s site inviable, he expects they might “[bring] suit to condemn the airport.” Even with Newton, though, KRON got the last laugh. Station general manager Harold P. See would write a guest column advocating again for San Bruno Mountain on behalf of his engineers, and noting that despite Newton’s attempt to cast See as a “black-hatted villain,” the “only black hat [he] ever owned wore out many years ago.”

Though they never strayed from their public-facing arguments about neighborhood aesthetics and community protection, the Chronicle’s incentive in transparently favoring one plan over the other was financial. In fact, The Chronicle Publishing Co. owned KRON and stood to profit handsomely if San Bruno was selected over San Francisco. It’s unclear in retrospect to what extent the campaign succeeded in maintaining public awareness of the dispute as it dragged on behind the scenes, or to win broader public favor over to the San Bruno plan before the tower began construction. There was a clear shift, however, in diminishing coverage as the 60s proceeded. This hinged primarily on decisions from the FAA in 1964 and the FCC in 1965 in favor of Mt. Sutro, effectively deciding the outcome. While Board of Supervisors disputes and lawsuits from outside parties attempting to arrest progress would continue to appear in the paper from 1966 onwards, the intensity of the coverage waned significantly. When ABC ultimately did sell the Avanzada property to the newly-formed consortium Sutro Tower, Inc., the major players comprising the nonprofit included both KGO and KRON, competing networks KPIX and KTVU, as well as other local media stations such as KQED.

The Chronicle did run the above advertisement for the tower on July 2, 1973, two days before it officially powered on. On July 5, the paper’s front page was dominated by Watergate and local Independence Day coverage. A small byline, “TV Tower’s First Day on Job,” ended the saga with a whimper and some sour grapes. “A barrage of boos, a few shrugs and some cheers,” it read: “That was the public reaction yesterday on the first day of television transmissions from the sky-high TV tower atop Mt. Sutro.” The article notes improved reception in some areas, particularly outside of San Francisco and at lower frequency broadcast channels. By contrast, Mrs. William F. Holmes, of 561 Las Palmos Dr. (directly south of Mt. Davidson, shielded from direct line of sight with the tower), is already quoted bemoaning the lost days when KRON, along with erstwhile partners KTVU and KQED, would send a signal to her home from San Bruno Mountain that was “perfect… just beautiful.” Following the move, she sighed, “all we get are these terrible wavy blobs of color.” KRON chief engineer Lee Berryhill offered consolation that in at least some cases, an antenna adjustment could solve the issue. “But if you don’t know what you’re doing, don’t just climb up on the roof,” he warned. “Get a professional antenna man to do the job for you.”

Nuts and Bolts

Fuzzy Reception

Herb Caen was, by and large, a San Francisco traditionalist. Caen coined the nickname Baghdad by the Bay for the city, and the columns he wrote for the Chronicle between 1938 and his death in 1997 reveled in the eccentric and timeless qualities that defined what he perceived to be its core character. He wasn’t opposed to change, and played a role in popularizing the terms “beatnik” and “hippie” as their subcultures rose to prominence. He was, however, challenged when he sensed affronts to the city’s architectural aesthetic. He complained when the Ferry Building was hidden behind the Embarcadero Freeway, and predictably, the completion of the Transamerica Pyramid and Sutro Tower within a year of each other pushed these same buttons. Caen would sporadically disparage both for years to follow. Caen sarcastically called the tower the “Pearl of Mount Sutro.” He is widely quoted online as having said of Sutro Tower, “I keep waiting for it to stalk down the hill and attack the Golden Gate Bridge.” He may have, though as above, he definitely wrote on December 19, 1972 that upon completion of construction it was “expected to stalk down the hill to mate with the Central Freeway.” Likewise, online comments credit Caen with having called Sutro Tower the “crate that the Transamerica Pyramid came in.” He is confirmed to have suggested on March 30, 1972 that the tower and the pyramid would be married, though they wouldn’t have children, “because they’d be ridiculed at school every time they took off their hats.” He made multiple references to a description offered by 11-year-old Lane Kannegieter: “the biggest roach-holder in the world.” Caen insisted that the functional benefits provided by the tower didn’t have much to offer him, as his Summer 1973 TV diet of Watergate hearings and Star Trek reruns was largely unimpacted by changes in reception. Caen did have the occasional soft spot for the tower, suggesting it could use a size 300 sweater then displayed in the window of Rochester Clothing at 3rd and Mission, and favorably comparing its appearance in the fog to a “three-masted schooner churning through billowing waves.” As he put it, “Not much, but better than nothing.”

A slightly more nuanced contemporary take appeared in the back pages of the Chronicle the day of the tower’s launch from TV columnist Terrence O’Flaherty, under the byline “The Steel Finger”:

In case you haven’t looked up recently, San Francisco has a new landmark on Mt. Sutro, hiding sometimes in the fog and occasionally vibrating like a giant harp in the wind…. This giant wire dream-machine points skyward like a big steel finger – or, for more spiritual folks, like a single candlestick waiting for a candle.

Regardless of its visual image, today at 6 a.m. it became the most important hunk of contemporary metal sculpture in the Bay Area because it is the communications focus for millions of people who live within the giant semicircle which its signal will transcribe from Fort Ross to the Monterey Peninsula.

Some people think the new antenna tower is a monstrous affront to the psyche and out of all proportion to the terrain. Others find it strangely beautiful like a big toy built from a giant Erector set. There are those who consider it a hazard to life and limb and there are those who think it is already obsolete because of the communications satellites that hover in space….

Closer to the truth, most people don’t care what it looks like as long as it improves the pictures of ball players, detectives, politicians, and beauty queens. And this it is expected to do for an estimated 90 per cent of its viewers….

In any case, San Francisco is now stuck with The Steel Finger so we might as well try to make it into a community landmark to be viewed with a mixture of amusement and affection in the same manner we tolerate the Ferry Building Fountain and pray that it works more efficiently than that pile of travertine and water-pipes dumped on our doorstep by a visiting Canadian.

Only the viewers will know for sure.

Typically for anthropology, it’s difficult to pinpoint the moment Sutro Tower’s reputation began to pivot away from O’Flaherty’s description: that of a technologic necessity whose aesthetic perception ranged from bemusement to disgust. Chronicle columnist Peter Hartlaub posited a generational divide in a 2012 column. For those born up to around the time of the Summer of Love, Hartlaub attributed the distaste to the efforts of his employer: “If you were reading newspapers when it went up, you're anti-Sutro. If you grew up in its shadow, you may be considering Sutro body art.” His example of the latter, Elly Jonez, indeed had an elaborate back tattoo of the project she justifiably suggested could never have been built after it was. Though she described it as “a symbol of San Francisco’s madness” and “another bad idea we've all grown to love,” she credited its designers with having “accidentally created a mystical object” that “grows more meaningful the more we look at it.”

John King wrote Portal, which explored the history of San Francisco’s Ferry Building. The book covers the building’s genesis as a proto-Grand Central Station for the Bay Area’s boat network, opposed at the outset by some who felt that using ferries to connect San Franciscans to the rail networks terminating in the East Bay meant surrendering to railroad monopolists. Once constructed, as intended, the Ferry Building served a vital function as a transportation hub for decades. However, with the dawn of the Roosevelt Era, King describes the building as not only supplanted functionally by the Bay Bridge (“tying San Francisco to the East Bay and (figuratively) to the continent beyond”), but symbolically by the Golden Gate Bridge, which usurped the Ferry Building as “the structure linked to San Francisco in the popular imagination, a hold that has only grown stronger with time.” Portal traces the Ferry Building as it was hidden behind the Embarcadero Freeway, exposed anew after the Loma Prieta earthquake, and reborn, functionally and aesthetically, as the hub of a revitalized Embarcadero and symbol of urban renewal.

Prior to Portal, King served as the Chronicle’s longstanding urban design critic, and in 2009 described Sutro Tower as a San Francisco icon “by default, rather than by architectural merit or public acclaim.” As an “unnatural finale to one of the world's most naturally beautiful urban settings,” he suggested it made sense that the tower had “never been a local favorite.” He did give some credit, noting that “our lean metallic alien serves as an aid to orientation,” before concluding that the tower is fortunately “so out of place, you can pretend it's not even there.” Over the ensuing 13 years, King may have been struck by the parallels between the Ferry Building and Sutro Tower: functional, if initially distrusted, structures whose appreciation grew as decades passed. By the publication of Portal, King did include Sutro Tower among a “constellation of local architectural stars” representing the area’s residents, an “ungainly yet arresting extension of the city’s third highest peak” which had eventually “become a cult favorite.” Even then, King named the Ferry Building as the only one of these landmarks to have experienced “profound shifts of meaning as the city and region evolved.” While he sees the Golden Gate Bridge as having played the “fog-shrouded seductress” from the start, and the Transamerica Pyramid as having won people over almost immediately, King suggests that Sutro Tower has simply “never had that much to say.”

How, then, to explain the groundswell?

Revival

Certainly, the tower’s ubiquity helps.

Photographer Joel Parsons recalled the sense omnipresence in Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, speaking to “scenes of everyday life… all tied together with the mountain giving a strong sense of place and cohesion.” In his own project, Thirty-Six Views of Sutro, Parsons spent nine years taking photos not only as an homage to Hokusai’s prints, but to emphasize the “strong sense of place” the tower likewise provides the city, and its role in “the beauty of this city and its incredible climate.”

The SF City Football Club, a supporter-owned soccer team in USL League Two, has played the bulk of its home games at Kezar Stadium, down the hill from Mount Sutro. Their primary badge features Sutro Tower along with silhouettes of the Transamerica Pyramid and a tower of the Golden Gate Bridge. In June 2025, the club announced a secondary badge more prominently featuring Sutro Tower. The social media announcement directly echoed Sutro Tower’s introductory press release from 1973, with copy speaking to the rationale: “Though once controversial, the tower has grown into a beloved part of the skyline – a symbol of resilience, eccentricity, and civic identity. Visible from nearly every neighborhood, it serves as a quiet, constant presence in the lives of San Franciscans, embodying the city’s blend of utility, individuality, and pride.” The announcement came just 6 weeks after Major League Soccer announced the planned addition to development league MLS NEXT Pro of Golden City Football Club, and with it, an exclusivity contract barring SF City and other local clubs from hosting more than one match a year at Kezar. Sutro Tower’s offer of visibility “from nearly every neighborhood” served as symbolic anchoring for the club as it unexpectedly began its search for a new permanent home.

The Illuminate art collective has been responsible for large-scale light projects in San Francisco for more than a decade, with a mission statement to bring “large groups of people together to create impossible works of public art that, through awe, free humanity’s better nature.” Their projects range widely in magnitude. The smallest are visible only within their immediate vicinity, including multicolored lights covering the bandshell in Golden Gate Park, or filling the Rose Window at Grace Cathedral. Larger, more monumental projects have included a rainbow laser display covering all of Market Street for Pride Weekend 2024, and working to reignite the light display across the Bay Bridge’s western span. However, their only project functionally visible to the entire city was their 2023 installation “loveAbove,” featuring “twelve lasers shooting upwards from the base of the iconic Sutro Tower in celebration of its 50th birthday on July 4.”

The Salesforce Tower was constructed between 2013 and 2018. Upon its opening, John King described the tower as a “well-tailored behemoth. Immense but understated. Overwhelming yet refined. A study in thick-walled minimalism that seems to hover more than soar.” He spoke to a number of promised but incomplete features at that time, some of which have since been completed – a welcome plaza, restaurant space, a connection to a completed Transit Center, and a glittering, LED-lined crown. Once these features had filled in, King argued, “the newcomer will begin to feel at home. And while it won’t ever gain visual swagger, you might come to like it more than you expect.” Thus far the skyscraper has certainly gained acceptance among locals, if not exactly fondness. As King put it, “It is what it is — a signature building done by a firm that works on four continents, hired by a developer of similarly wide reach.” He also admitted that “the curved shaft… has undeniable phallic connotations,” and though he described this as a nod to classical obelisks – again, it may be – this has certainly defined the project’s lingering reputation among locals. Joel Parsons references the building’s “ominously ever present bulbous tip,” and ongoing projects like JusttheTipSF point to a omnipresence which, at least as of 2025, has yet to materialize into a sense of connection or fondness for San Franciscans. Perhaps this will come. Hartlaub’s article, after all, spoke to a growing connection to Sutro Tower among the city’s youth that was (seemingly) only picking up steam 40 years after construction had begun. Perhaps, though, it speaks to something intrinsic to Sutro Tower which draws people beyond merely its ubiquity. John King may not have been incorrect in describing the tower as “so out of place, you can pretend it's not even there”; yet clearly, many are happy not to.

In addition to tower-tattooed Elly Jonez, Peter Hartlaub argued for the hold Sutro Tower possessed over young San Franciscans of 2012 by quoting then-27-year-old writer Kevin Montgomery. Montgomery prefaced his feelings about Sutro Tower by referencing the Golden Gate Bridge. Calling it San Francisco’s answer to the Hollywood Sign, Montgomery recalled the bridge’s appearance in the title sequence of Full House, and named the landmark “something that everyone knows about.” In comparison, Montgomery ironically called the physical object formally vertically furthest from the surface of the Ocean and Bay “more underground.” He added, “You have to know San Francisco. If you see someone with Sutro on a T-shirt, you know they have intimate knowledge of the city.” As he says, there is insider signaling to be plied using the imagery of Sutro Tower: native New Yorkers likely spend little time in Statue of Liberty t-shirts, after all, and a San Franciscan could be forgiven (even if wrong) for finding a cable car hat somewhat gauche. To suggest this is all, though, would be to undercut a uniquely strong connection between San Francisco and its eccentrics, which arguably serves as one of its most important cultural hallmarks.

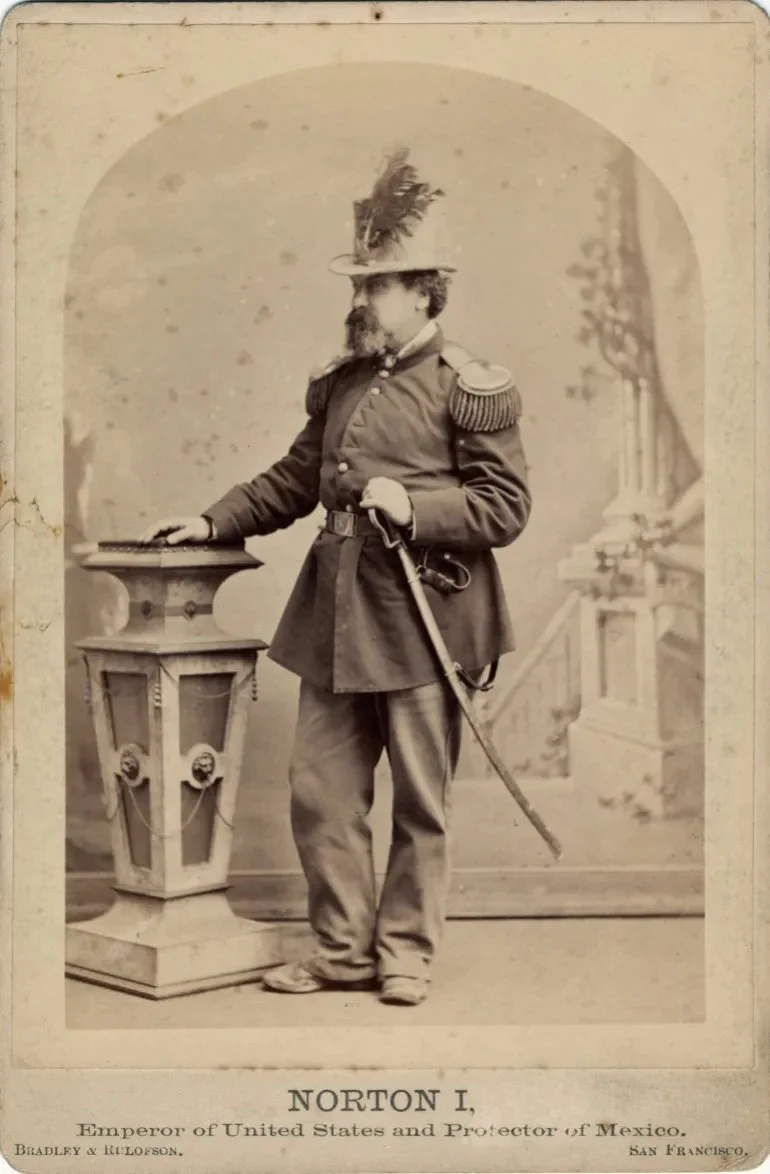

Joshua Abraham Norton arrived in San Francisco in 1849, possibly aboard one of the very ships still buried under infrastructure in the city’s northwest corner. He had a successful run in commodities and real estate before a disastrous attempt to turn himself into a rice magnate culminated in bankruptcy in 1856. Three years later, Norton provided a letter to the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin declaring himself “Emperor of these United States.” Norton I’s attempts to ingratiate himself with world leaders and marry Queen Victoria proved unsuccessful, but while he died materially poor, he was unequivocally beloved in his adoptive hometown. San Franciscans provided Norton with free food and transportation, printed his proclamations, and sold souvenirs with his likeness. His obituary in the Chronicle began with the words “The King is Dead.”

Claude the albino alligator hatched in Louisiana on September 15, 1995. In addition to lacking native camouflage with his glaringly white hide, Claude’s ocular albinism rendered him functionally blind. After an upbringing spent at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm, Claude moved to the California Academy of Sciences in 2008. A disastrous early attempt to house him with a non-albino alligator ended with Claude sustaining a bite from his swampmate resulting in an amputated finger. Unable to hunt – to protect himself even from prospective lovers, let alone foes – Claude spent the rest of his life with snapping turtles for neighbors. Against all odds, Claude became an emblem of his institution, featuring in clothing, magnets, tote bags, and even children’s books. He also became an emblem of his adoptive hometown, finishing behind only San Francisco’s iconic wild parrots and sea lions in a 2023 citywide contest to nominate an official animal. Claude’s 30th birthday in September 2025 was cause for a monthlong, citywide celebration, and his sudden death from liver cancer that December likewise a cause for citywide mourning.

Among the wealthiest citizens San Francisco ever made was journalism magnate William Randolph Hearst. After receiving the San Francisco Examiner from his father, Hearst famously dedicated his life to succeeding in journalism by any means necessary, embodying the spirit of the epithet famously attributed to him – “You furnish the pictures, I'll furnish the war” – even if he likely never said it. Hearst’s empire began its expansion by consuming its competition, including the very Daily Evening Bulletin to whom Norton I had presented his proclamation. Hearst’s family would remain rooted in the Bay, notoriously including his granddaughter, who was kidnapped from her Berkeley apartment in 1974. Hearst himself, however, had long left the area, settling in a Julia Morgan-designed castle near San Luis Obispo. There, he famously hoarded all of the treasures money could buy, away from prying eyes. There are surely countless reasons Hearst opted to build his fortress 250 miles from San Francisco, but it is curious to contrast him with perhaps his nearest authentically San Franciscan analogue: Adolph Sutro himself. Sutro, too, amassed a surreal fortune, built a mansion full of treasures, and left behind a complex, messy estate for posterity to sort out. Sutro opted to stay, however. He left mountains, parks, and bathhouses with his name on them that continue to shape the city 125 years later. Perhaps most San Franciscan of all, Sutro not only built his mansion-museum within city limits, but opened the grounds for normal residents to tour and built the trains that not only enabled them to visit, but ultimately, to live nearby.

Sutro Tower remains as unconventional a landmark in 2025 as it was upon completion in 1973, and the classic descriptors still fit. A “steely structure” with a “metallic snout”; “The Steel Finger,” a “giant Erector set”; a “lean metallic alien,” an “ungainly yet arresting extension” of San Francisco’s famous hills. Peter Hartlaub’s 2012 essay insightfully shares:

The reasons for loving Sutro, interestingly, are often the same as the previous generation's

reasons for hating it.Residents moaned in the 1970s:

It looks like a metal claw coming out of the middle of the city.

Sutro backers cheer in 2012:

It looks like a metal claw coming out of the middle of the city!

Sutro Tower was perceived in its earliest years as a harbinger of a future that would strip San Francisco of its charm. A city that still bore witness to memories of Emperor Norton and an isolated existence on a bridgeless peninsula looked at the “giant wire dream-machine” and felt the same dread its ancestors had when they built the Ferry Building. Perhaps they worried that everything around them would start to look like Sutro Tower. Instead, nothing did. The tower’s unlikeliest accomplishment was successfully transforming itself from a stain of conformity to a symbol of the very noncomformity the city has never stopped suggesting it loves. And it did so effortlessly, standing stationary, its lights blinking above the fog.

Bibliography

The most important source for this and likely any other project on Sutro Tower is the website compiled by David July – SutroTower.org – a project so comprehensive and informative that I almost abandoned this project upon discovering it. Other sources are included below, by section:

The Name Behind the Tower

Brand, Gregor. “Adolph Sutro.” Eifel Zeitung, 9/2/2015.

Grieg, Michael. "A Gingerbread Palace Crumbling." San Francisco Chronicle, 11 April 1974, 3.

Hayes, Elinor. "Sutro Tower to Replace Historic Mountain Villa." Oakland Tribune, 19 October 1969.

McLaughlin, Mark. “Crazy Sutro: Engineer with tunnel vision.” Tahoe Guide, 15 June 2016.

Waves and Hills

Schneider, John F. "Early Broadcasting in the San Francisco Bay Area: Stations That Didn’t Survive: 1920-1925."

Wikipedia: Cable TV, Line-of-sight Propagation, Television Broadcaster, Terrestrial TV

Turf War and Fuzzy Reception

Archival Newspaper Articles (all San Francisco Chronicle, except San Francisco Examiner article denoted by *)

Anonymously Authored, listed chronologically

"Mt. Sutro TV Proposal: Opposition to KGO 'Eiffel Tower." 10 June 1957, [page] 6.

"How the Tower Would Look." 11 June 1957, 6.

"Offer by ABC: San Bruno TV Tower Backed." 11 July 1962, 4.

"TV Hearing: Opposition to Mt. Sutro Tower." 12 July 1962, 5.

"TV Tower Hearing to Continue in Washington." 13 July 1962, 5.

"City Planners: 2 Oppose Height of Sutro Tower." 20 July 1962, 4.

"Aviation Hearing: Mt. San Bruno TV Site Backed." 21 July 1962, 9.

"TV Tower Plea Fought by United Air." 13 October 1962, 7.

"KGO Seeks TV Tower on Mt. Sutro." 27 January 1966, 48.

"Ruling on Mt. Sutro TV Tower." 11 March 1966, 28.

"Board's Decision on TV Tower." 17 May 1966, 42.

"KRON Gets OK to Move Antenna." 6 December 1969, 32.

"City Planners OK Plans for TV Tower." 11 September 1970, 15.

"Environmental Unit: A Suit to Block Sutro TV Tower." 24 November 1971, 4.

"USF Students Challenge Mt. Sutro TV Tower." 13 January 1972, Section A, Page 13.

"Sutro Tower Opponents Told to Hurry." 26 January 1972, 10.

"Judge Gives Go-Ahead to Sutro Tower." 27 January 1972, 2.

"The Sutro TV Tower -- On the Beam by July 4." 28 June 1973, 2.

"PUBLIC NOTICE." 2 July 1973, 11.

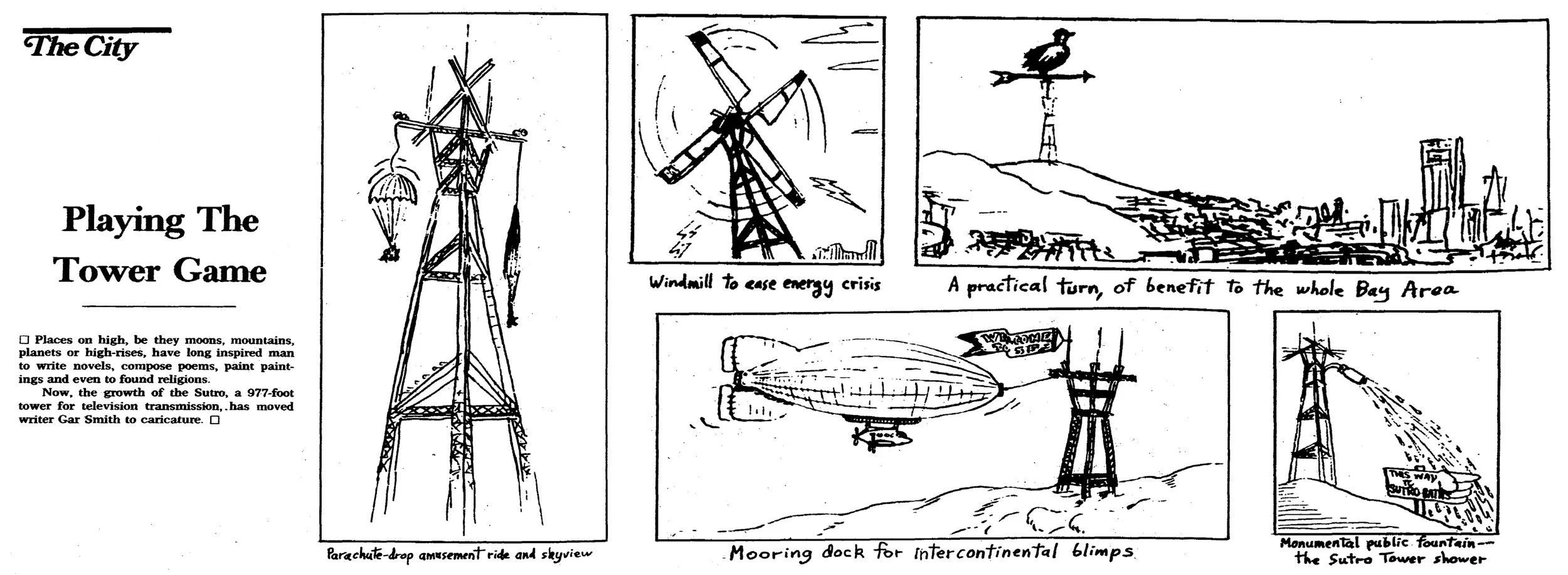

"The City: Playing the Tower Game." 19 August 1973, California Living Magazine, 6.

Credited, listed chronologically by author

Caen, Herb

"One Thing After Another." 8 February 1972, Second Section, Page 23.

"Friday's Fractured Flicker." 3 March 1972, Second Section, Page 25.

"More Cheap Thrills." 30 March 1972, Second Section, Page 25.

"Just Foolin' Around." 19 December 1972, Second Section, Page 25.

"Out of My Mind." 8 April 1973, Sunday Punch, Page 1.

"Playing Catchup." 16 July 1973, Second Section, Page 21.

"Funny Old Town." 18 July 1973, Second Section, Page 31.

"Clicks from the Cables." 3 September 1974, Second Section, Page 23.

Doss, Margot Patterson

"The Castle in the Forest." Bonanza Magazine. 11 March 1962, 7.

Newton, Dwight

"The Picture Is Bleak." 21 November 1965. Section II, Page 4.

"TV Tower Is Still Up in the Air." 6 February 1966. Section II, Page 5.

"KRON's Side of the TV Tower." 13 February 1966. Section II, Page 5.

"Are You in the New TV Picture?" 22 July, 1973, 1 and 4.*

O'Flaherty, Terrence

"The Steel Finger." 4 July 1973, 14.

Zane, Maitland

"TV Tower's First Day on Job." 5 July 1973, 1 and 20.

Hartlaub, Peter

“Stature of Sutro Tower rises.” 28 May 2012.

“Sutro Tower at 50: From aesthetic ‘horror’ to San Francisco icon.” 3 August 2023.

King, John

“Good reception, little affection.” 29 November 2009.

Portal: San Francisco’s Ferry Building and the Reinvention of American Cities. Norton & Co., 2024.

“Salesforce Tower - underwhelming despite its size.” 9 January 2018.

Revival

Claude the Albino Alligator (RIP)

Joel Parsons’ Thirty-Six Views of Sutro

Adapted from California Living Magazine, Sunday Chronicle/Examiner, 19 August 1973

Special thanks for Teddy for convincing me that I had something valuable to add to a topic that has already been documented so beautifully, and that this was a project worth following through on. I’m glad I did ❤️